Abstract

Although sinus vein thrombosis is rare in childhood, drugs play an important role in the etiology. Sinus vein thrombosis should be excluded with urgent imaging in the presence of headache, weakness, and papilledema lasting longer than 1 week, especially in adolescent girls who require hormonal medication due to oligomenorrhoea. If thrombosis is detected in these cases, urgent surgical intervention will be a life-saving approach if the thrombosis and infarct area in the brain are widespread and lead to herniation. We discussed the recovery of a 17-year-old obese girl after the use of oral contraceptives due to menstrual irregularity, the place of surgical approach in the treatment of thrombosis, and the recovery of shifting and herniation due to diffuse sinus vein thrombosis after emergency decompressive surgery. Consent was obtained from the patient’s parents beforehand.

Keywords: adolescent, cranial decompression, hormone, sinus vein thrombosis

INTRODUCTION

Cerebral sinus vein thrombosis (SVT) is an uncommon complication in children, with a prevalence of 0.4-0.7 per 100,000, but it can cause morbidity and mortality if not diagnosed and treated early.1 While infections are the most common cause of SVT, cardiac diseases, renal diseases, malignancies, and drugs are other causes.1,2

It is difficult to recognize SVT because of the diversity of clinical symptoms and findings. The superior sagittal sinus, transverse sinus, and sigmoid sinus are most commonly affected.3 Patients may present with different clinical pictures, including headache, confusion, seizure, focal neurological findings, encephalopathy, and seizure depending on the localization of the affected brain. Anticoagulant treatment may not be adequate, especially in the presence of rapidly changing findings such as clouding of consciousness and a decrease in coma scale, depending on the extent of thrombus and infarction; emergency surgical intervention may be planned in cases to prevent an increase in intracranial pressure, shifting, and herniation.1

We report the successful management of life-threatening SVT after oral contraceptive (OCS) use in an adolescent girl with emergency surgical decompression and anticoagulant therapy.

CASE REPORT

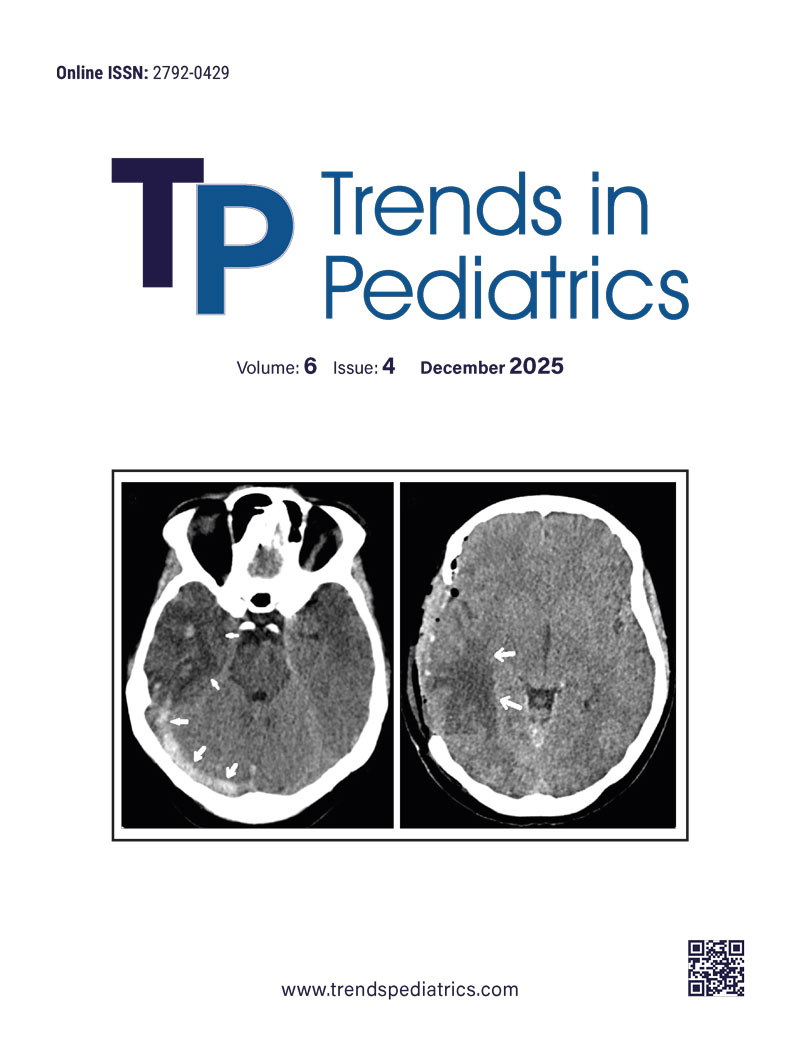

A 17-year-old female patient presented to the emergency department with complaints of severe headache for 1 week and slowed movements and left extremity weakness that started 1 day ago. Physical examination revealed a body mass index of 26 kg/m2, an obese appearance, and signs of hirsutism. In vital signs, blood pressure was 120/75 mmHg, pulse rate was 70 beats/minute, and temperature was 36.7°C. Neurological examination revealed consciousness and central facial paralysis on the right, muscle strength was 2/5 in the left lower and upper extremities, and other system examinations were normal. Glasgow Coma Scale was 10. Papilledema was detected. Laboratory findings included hemoglobin: 10.2 g/dL, MCV: 83.5 fL, platelet count: 13,000/mm3, WBC: 3350/mm3, and absolute neutrophil count: 1750/mm3, sodium: 135, potassium: 3.8, creatinine: 0.68. Prothrombin time: 13 seconds, D-Dimer: 3.3 was high. Brain tomography performed at an external center revealed no pathology. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain performed in our center at his presentation to us with complaints of increased headache and weakness revealed changes compatible with diffuse thrombus in the right transverse sinus, sigmoid sinus and jugular vein (Figure 1), signal increase and oedema compatible with venous hemorrhagic ischemia in the supratentorial right temporal, right basal ganglia and thalamic region (Figure 2), and changes suggestive of right to left shifting and uncal herniation. When her history was questioned, it was learnt that she had no previous thrombosis and no known systemic disease, and she had been using OCS containing 0.02 mg ethinylestradiol and 3 mg drospirenone for 1 year due to oligomenorrhoea. The patient underwent anterior temporal lobectomy and thrombectomy with urgent surgical decompression due to diffuse thrombus, shifting, and herniation findings, and altered consciousness on brain MRI (Figure 2)

Anti-nuclear antibody, perinuclear anti-cytoplasmic antibody, anti-cytoplasmic antibody, anticardiolipin antibody IgM and IgG, and Lupus anticoagulant were found to be negative. Antithrombin III, Protein S, and Protein C levels were normal. Factor V Leiden and prothrombin 20210A mutations were not detected. Low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) was started with the diagnosis of right lateral SVT. The patient was intubated for 24 hours after the operation and was conscious after extubation. Left upper extremity muscle strength was 1/5. On the fifth postoperative day, it was observed that the upper extremity muscle strength of the patient who was taken to physical rehabilitation increased significantly (4/5). On the 10th day of anticoagulant treatment, the patient’s complaints improved almost completely, and the patient was discharged with an outpatient follow-up planned. No recurrence of SVT was observed during prophylactic anticoagulant treatment for six months.

DISCUSSION

Although SVT may be observed at all ages, it is most commonly observed in the neonatal and young adult age group. It is 3 times more common in women.4 It is observed secondary to prothrombotic conditions, including pregnancy, puerperium, and OCS use.5-8 In patients with hereditary thrombophilia risk factors, triggering factors, including systemic diseases, trauma, drug use (including hormones and steroids), infection, and malignancies predispose to thrombosis formation.9 OCSs have been reported to increase the risk of thromboembolism. In this article, the development of life-threatening SVT in an obese adolescent girl after OCS use and its correction with decompressive surgery is presented because it is a rare case.

When focal neurological symptoms and signs develop in the presence of new-onset severe headache and seizures in children, SVT should be considered, especially if risk factors are present, and urgent investigations and treatments should be planned for the diagnosis. In a study by Gosk-Bierska et al. the most common symptom was headache, with a rate of 87%, and the most common examination finding was papilledema, with a rate of 55%.10 The most commonly used radiological examinations for the diagnosis of cerebral thrombosis are brain MRI and MR venography.4 Brain computed tomography (CT) is an easily accessible imaging modality, but its role in the diagnosis of SVT is limited. In 25% of patients, neurological examinations may be completely normal, and CT may be normal.11 In the present case, although no pathology was detected initially on brain tomography performed after presentation with severe headache and weakness lasting 1 week, the presence of papilledema indicated that MRI was more useful in detecting thrombus.

Although SVT is rare, it may result in high mortality and morbidity in the absence of early diagnosis and treatment. The presence of increased intracranial pressure and venous infarcts accompanying diffuse thrombus is a dangerous picture, and the patient may die within hours due to herniation. The presence of impaired consciousness and cerebral hemorrhage are considered to be markers of poor prognosis. The priority is to stabilize the patient and prevent or reverse cerebral herniation.12,13 For this purpose, head elevation, sedation, administration of mannitol or 3% NaCl, and hyperventilation are emergency approaches.14 If herniation cannot be prevented despite these, surgical removal of hemorrhagic infarction or decompressive hemicraniectomy may be required in patients with unilateral hemispheric lesions with the expectation of a better functional recovery.15 In this case, emergency decompressive surgery and thrombectomy were preferred in the first stage because the cause of increased intracranial pressure was diffuse thrombosis, and shifting and herniation were found on brain MRI. In addition, anticoagulant and thrombolytic therapies are used in the medical treatment of cerebral vein thrombosis.16 In clinical practice, the use of anticoagulants such as intravenous heparin or LMWH may contribute to the control of intracranial pressure. In different studies, LMWH treatment monitored with anti-factor Xa levels has been shown to be safe. LMWH, which was started after surgery in our patient, led to rapid clinical improvement and discharge in a short time. No recurrence of SVT was observed during prophylactic anticoagulant treatment for six months.

The importance of imaging modalities such as MR and MR Venography at the time of clinical suspicion, even if brain tomography is normal in patients with headache, is seen in this case. There is a need for studies with more case series in the recognition and follow-up of cerebral thrombosis cases.

In conclusion, in the presence of clinical findings such as severe headache lasting more than 1 week, altered consciousness, and papilledema in obese adolescent girls requiring hormonal drug use, urgent imaging should be planned for early diagnosis of SVT, and the decision for medical or urgent surgical treatment should not be delayed.

Ethical approval

No ethics committee was obtained for the case report, and informed consent was obtained from the patient and her family.

Source of funding

The authors declare the study received no funding.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Kaya Z. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. In: Orhaner B, editor. Thrombosis in Childhood. 1st ed. Ankara: Türkiye Clinics; 2020. p. 79-85.

- Guzelkucuk Z, Karapınar DY, Gelen SA, et al. Central nervous system thrombosis in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia in Turkey: A multicenter study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2023;70:e30425. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.30425

- Renowden S. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Eur Radiol. 2004;14:215-26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-003-2021-6

- Ehtisham A, Stern BJ. Cerebral venous thrombosis: a review. Neurologist. 2006;12:32-8. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nrl.0000178755.90391.b6

- Bousser MG, Chiras J, Bories J, Castaigne P. Cerebral venous thrombosis-a review of 38 cases. Stroke. 1985;16:199-213. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.str.16.2.199

- Dzialo AF, Black-Schaffer RM. Cerebral venous thrombosis in young adults: 2 case reports. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82:683-8. https://doi.org/10.1053/apmr.2001.19244

- Allroggen H, Abbott RJ. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Postgrad Med J. 2000;76:12-5. https://doi.org/10.1136/pmj.76.891.12

- Lanska DJ, Kryscio RJ. Stroke and intracranial venous thrombosis during pregnancy and puerperium. Neurology. 1998;51:1622-8. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.51.6.1622

- Saposnik G, Barinagarrementeria F, Brown RD, et al. Diagnosis and management of cerebral venous thrombosis: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2011;42:1158-92. https://doi.org/10.1161/STR.0b013e31820a8364

- Gosk-Bierska I, Wysokinski W, Brown RD, et al. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis: Incidence of venous thrombosis recurrence and survival. Neurology. 2006;67:814-9. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000233887.17638.d0

- Kaya D. Diagnosis and treatment of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Turk J Neurol. 2017;23:94-104. https://doi.org/10.4274/tnd.79923

- Kimber J. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. QJM. 2002;95:137-42. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/95.3.137

- Bushnell C, Saposnik G. Evaluation and management of cerebral venous thrombosis. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2014;20:335-51. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.CON.0000446105.67173.a8

- Fischer C, Goldstein J, Edlow J. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis in the emergency department: retrospective analysis of 17 cases and review of the literature. J Emerg Med. 2010;38:140-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2009.08.061

- Filippidis A, Kapsalaki E, Patramani G, Fountas KN. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis: review of the demographics, pathophysiology, current diagnosis, and treatment. Neurosurg Focus. 2009;27:E3. https://doi.org/10.3171/2009.8.FOCUS09167

- Duman T, Uluduz D, Midi I, et al. A multicenter study of 1144 patients with cerebral venous thrombosis: the VENOST study. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2017;26:1848-57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2017.04.020

Copyright and license

Copyright © 2025 The author(s). This is an open-access article published by Aydın Pediatric Society under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, provided the original work is properly cited.