Abstract

Objective: Adolescent obesity is a significant global health issue impacting both physical and psychological health, especially body image perception. This study investigates the correlation between obesity and body image perception in adolescents with a Body Mass Index (BMI) over the 95th percentile, emphasizing gender disparities and psychosocial consequences.

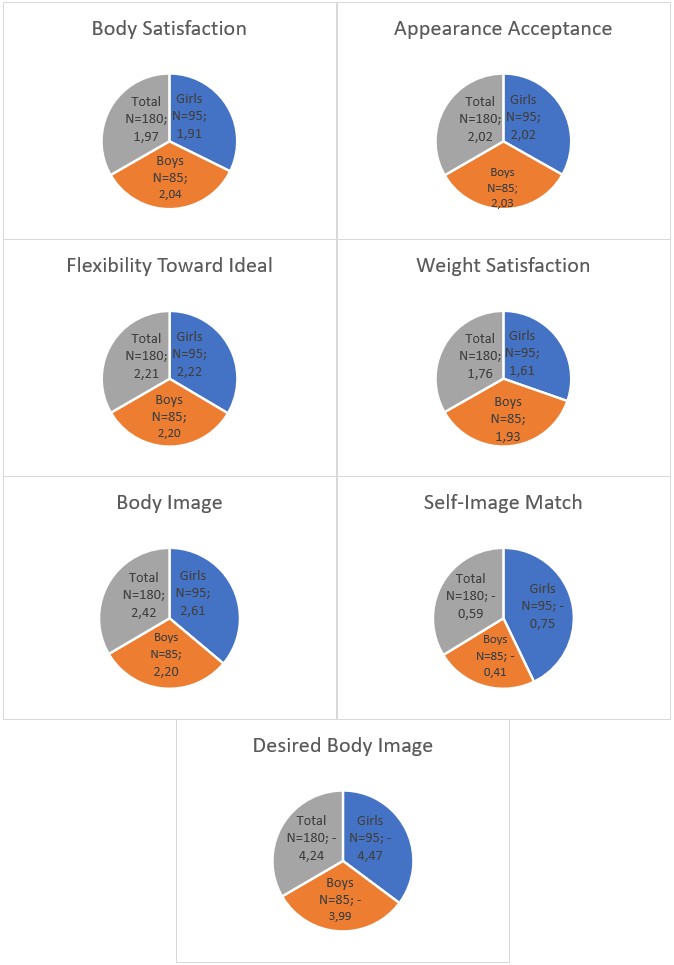

Method: A cross-sectional study was conducted in pediatric clinics, which included 180 obese adolescents (95 females and 85 males). Anthropometric measurements, including weight, height, waist circumference, and neck circumference, were recorded. The Child Body Image Scale (CBIS) and the Child Body Satisfaction Scale (CBSS) are two standardized instruments that have been employed to evaluate body image. SPSS version 25.0 was employed to conduct statistical analyses.

Results: Females experienced significantly more body dissatisfaction than their male counterparts (p < 0.05). Girls perceived themselves as overweight and aspired to a slimmer physique, resulting in a substantial discrepancy between their perceived and ideal body images. Males exhibited a comparatively higher level of physical satisfaction. A significant negative correlation exists between age and body satisfaction (r = -0.40, p < 0.01); dissatisfaction is more prevalent among females as they age.

Discussion: These results underscore the necessity for prompt psychological therapies to address body dissatisfaction in obese teenagers. Negative body image is associated with depression, anxiety, and eating disorders. Gender disparities indicate the necessity for customized therapies, particularly for girls who are more susceptible to adverse self-image.

Conclusion: This study highlights the strong relationship between childhood obesity and negative body image. The findings show that children with obesity are more likely to feel dissatisfied with their body appearance, which may negatively affect their emotional well-being and self-esteem. The use of validated measurement tools strengthens the reliability of the results. Early identification of body image concerns can improve both mental and physical health outcomes in this vulnerable population.

Keywords: adolescent obesity, self-perception, psychological well-being, body image

INTRODUCTION

Adolescent obesity is a burgeoning global health issue that impacts not only metabolic and physiological health but also psychological well-being. Obesity is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as an excessive accumulation of body fat that creates health risks. In individuals under the age of 18, the 95th percentile of Body Mass Index (BMI) for age and sex is a critical threshold for obesity classification. Although the metabolic consequences of obesity, including insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, have been extensively investigated, its influence on psychological and psychosocial dimensions, particularly body image perception, is less frequently addressed in clinical practice.1,2

Adolescent obesity is correlated with body image dissatisfaction (BID), affecting social interactions, mental health outcomes, and self-esteem. Research has shown that body dissatisfaction is a common occurrence in childhood and tends to increase during adolescence, particularly in individuals with elevated BMI percentiles.3,4 Obese adolescents are more prone to misperceiving their body size, leading to maladaptive behaviors such as emotional eating, unhealthy dieting, and insufficient physical activity.5,6

The sociocultural emphasis on slimness, amplified by media and peer influences, intensifies negative body image perceptions in adolescents. Research indicates that negative body image significantly precedes psychological distress, including anxiety, depression, and eating disorders, underscoring the need for early intervention and support systems.7,8 Gender disparities are significant; while both sexes are susceptible to its adverse effects, adolescent females are more prone than males to experience body dissatisfaction.9,10

This study was conducted to examine body image in adolescents aged 18 years and younger with obesity (BMI ≥ 95th percentile), with a particular focus on gender differences and the psychosocial effects of excess weight. Childhood obesity is not merely a physical health issue but is also closely associated with psychological distress, reduced self-esteem, and body dissatisfaction. Understanding how adolescents perceive their bodies can provide important insights into the emotional burden of obesity and highlight the necessity of comprehensive intervention strategies that address both the physical and psychological aspects of care.

MATERIAL-METHOD

Study design and participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted between April 2025 and May 2025 at Kartal Dr. Lütfi Kırdar City Hospital, Istanbul, Türkiye. The study population consisted of adolescents aged 9–18 years who applied to the pediatric outpatient clinic during this period. Participants with a BMI at or above the 95th percentile for age and sex, according to national reference standards, were included in the obesity group.

Inclusion criteria

- Age between 8 and 17 years

- BMI ≥ 95th percentile for age and sex

- Voluntary participation with parental/guardian consent

Exclusion criteria

- Diagnosed psychiatric disorders

- Use of medications affecting weight or appetite

- History of bariatric surgery or weight management intervention within the last 6 months

- Incomplete questionnaire data or missing anthropometric records

Data collection and measurement

Anthropometric measurements were taken for all participants who agreed to participate in the study. Height was measured using a Harpenden stadiometer and recorded to the nearest 0.1 cm. Weight was recorded using a calibrated digital scale and again rounded to the nearest 0.1 kg. BMI was calculated by dividing weight in kilograms by height in meters squared (kg/m²). BMI percentiles were determined according to national reference standards specific to age and gender, and participants were classified.11

All participants completed two validated self-report questionnaires: the CBIS (Children’s Body Image Scale) and the CBSS (Children’s Body Satisfaction Scale), which were used to assess body image perception and satisfaction, respectively. Using the Child Body Image Scale (CBIS) developed by Truby and Paxton (2002), which comprises figure drawings that are gender- and age-specific for children between the ages of seven and twelve, body image perception was evaluated.12 The CBIS has been reported to have an internal consistency of Cronbach’s alpha = 0.84, which suggests that it is highly reliable. The scale assists in the identification of the discrepancy between the ideal and perceived body shape. The Child Body Satisfaction Scale (CBSS), which was developed by Keven-Akliman and Özabacı was employed to measure body satisfaction by evaluating satisfaction with specific body areas. The scale has exhibited exceptional psychometric properties, as evidenced by a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.87.12

The tools were administered in a quiet clinical environment under the supervision of the participants’ parents to ensure comprehension and comfort. The reliability and validity of the scales have been previously established in pediatric populations.

The study was started after ethics committee approval was obtained (Approval Number: 2025/010.99/14/20). After informed consent was obtained from the participants and their families, the questionnaire form was given to the participants, and they were asked to complete it.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics version 25.0. The normality of data distribution was determined by evaluating skewness and kurtosis values, with values between ±2 indicating a normal distribution. For variables showing a parametric (normal) distribution, the Student t-test was applied, while the Mann-Whitney U test was used for non-parametric (non-normal) data. Pearson correlation analysis was performed to evaluate the relationships between continuous variables. A statistical significance threshold of 0.05 was accepted as the type I error level.13

RESULTS

A total of 95 girls and 85 boys participated in the study. The mean values of age, height, weight, and height circumference of the participants are shown in Table 1.

| Table 1. Age and Anthropometric measurements | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Z: Mann-Whitney U Test, T: Independent Sample T Test, *p<0.05: Significant at the level | ||||||||||

| Age |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Weight (kg) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Weight(p) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Height (cm) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Height (p) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Waist Circumference (cm) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Waist Circumference (p) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Body Mass Index (cm) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Body Mass Index (p) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Neck Circumference |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The study included 180 children, with 95 girls (52.8%) and 85 boys (47.2%). The mean age of participants was 12.19 ± 3.11 years. Boys had a significantly higher mean weight (84.80 ± 33.05 kg) than girls (70.30 ± 17.39 kg) (p < 0.05). Similarly, boys had a greater height (160.80 ± 18.84 cm) compared to girls (153.53 ± 12.00 cm) (p < 0.05). BMI was also significantly different between the two groups, with boys exhibiting a higher mean BMI (31.45 ± 7.48 kg/m²) compared to girls (29.42 ± 4.60 kg/m²) (p < 0.05).

Waist circumference and neck circumference measurements followed similar trends, with boys showing significantly higher values than girls (p < 0.05). However, no statistically significant difference was found in BMI percentiles between boys (98.98 ± 1.20) and girls (97.40 ± 4.79) (p > 0.05), indicating that both groups were classified within the obese category.

There was no significant difference between the ages and percentiles of anthropometric measurements of boys and girls (p>0.05). There was a significant difference between weight (kg), height (cm), height (p), waist circumference (cm), body mass index (kg/m2), neck circumference (cm) values (p<0. 05); weight (kg), height (cm), height (p), waist circumference (cm), body mass index (kg/m2), neck circumference (cm) values of boys were found to be higher than girls.

100.0% of girls (average age: 11.98 years) perceived themselves as heavier than they actually were. In terms of the body image they think most resembles themselves, 48.4% perceived themselves as thinner than they actually are, while 51.6% assessed themselves accurately. When it comes to ideal body image preferences, all girls preferred a slimmer body type than their current appearance (Table 2).

| Table 2. Evaluation of body image and reality perception according to gender and age | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Girls N=95 | Body Image Perception | ||||||

| Perceiving oneself as smaller than one's size |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Right choice |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Perceiving oneself to be more overweight than one is |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Image Perception Most Similar to Self | |||||||

| Perceiving oneself as smaller than one's size |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Right choice |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Perceiving oneself to be more overweight than one is |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Perception of the Image He Wants to Be Like | |||||||

| Perceiving oneself as smaller than one's size |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Right choice |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Perceiving oneself to be more overweight than one is |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Boys N=85 | Body Image Perception | ||||||

| Perceiving oneself as smaller than one's size |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Right choice |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Perceiving oneself to be more overweight than one is |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Image Perception Most Similar to Self | |||||||

| Perceiving oneself as smaller than one's size |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Right choice |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Perceiving oneself to be more overweight than one is |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Perception of the Image He Wants to Be Like | |||||||

| Perceiving oneself as smaller than one's size |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Right choice |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Perceiving oneself to be more overweight than one is |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Total N=180 | Body Image Perception | ||||||

| Perceiving oneself as smaller than one's size |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Right choice |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Perceiving oneself to be more overweight than one is |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Image Perception Most Similar to Self | |||||||

| Perceiving oneself as smaller than one's size |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Right choice |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Perceiving oneself to be more overweight than one is |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Perception of the Image He Wants to Be Like | |||||||

| Perceiving oneself as smaller than one's size |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Right choice |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Perceiving oneself to be more overweight than one is |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Among boys, 4.7% (average age: 8.00 years) perceived their body size accurately, while 95.3% (average age: 12.64 years) perceived themselves as heavier than they actually were. When asked which body image they most closely resembled, 34.1% perceived themselves as thinner than they actually were, 55.3% made the correct choice, and 10.6% perceived themselves as overweight. Regarding the ideal body image they aspired to, 100.0% selected an image that was thinner than their actual body measurements (Figure 1).

DISCUSION

This study examined how body image perception changes with age in obese children and how body image dissatisfaction increases, especially in girls. The findings of our study show that girls’ satisfaction with their bodies decreases as they get older, and their body image perceptions are negatively affected. This is consistent with many studies in the literature.14,15

The findings of our study are consistent with international research showing that body image perception is a widespread problem among adolescents. A study examining adolescents from six different countries found that body dissatisfaction is widespread and significantly associated with sociodemographic factors and social media use.16 These international findings emphasize the universality of body image concerns among adolescents and highlight the need for culturally adapted interventions. In this context, our study provides valuable data on Turkish adolescents, a population that is underrepresented in global research. By providing insights into Turkish adolescents’ perceptions of body image and levels of dissatisfaction, our study contributes to understanding how cultural and regional factors influence adolescents’ body image.

It is known that, especially during adolescence, body image concerns increase, and this has serious effects on psychological health.17 The increase in body dissatisfaction in girls with age has been associated with problems such as eating disorders, depression, and low self-esteem.18 In this context, in our study, it was determined that 100% of the girls perceived themselves as overweight, and the image they wanted to resemble represented a thinner body structure. The discrepancy between the perceived body image and the ideal body image was greater in girls, suggesting a higher tendency toward negative body perception. In contrast, boys were more likely to accept their body image as it is, despite their high BMI values. These differences may reflect sociocultural influences on body ideals and should be considered when designing gender-sensitive interventions for obesity in adolescents.

Disturbances in body image perception are an important risk factor, especially for eating disorders. Studies show that individuals with body image dissatisfaction are more likely to develop eating disorders.19 In addition, negative body image perception is strongly associated with depression and may increase suicidal thoughts.20 In our study, a negative correlation was found between body image perception and satisfaction level, and it was shown that body satisfaction decreased with increasing age.

Comparisons between genders showed that girls had lower body satisfaction scores compared to boys. This is a finding frequently emphasized in the literature. The fact that girls are more affected by media, peer pressure, and social perceptions of beauty may cause deterioration in body image perception to become more pronounced.21 In boys, although there is some decrease in body image satisfaction with age, this is less pronounced compared to girls. Age was negatively correlated with body satisfaction in both genders (r = -0.40, p < 0.01), suggesting that as age increased, body dissatisfaction became more prominent. This effect was stronger among girls, indicating that adolescent girls with obesity experienced higher psychological distress related to their body image compared to boys.

Four Turkish studies utilize survey data to investigate the relationship between adolescent obesity and body image perception. Ozmen et al. indicate that adolescents’ self-reported overweight status correlates more significantly with body dissatisfaction, diminished self-esteem, and depression than with objective BMI metrics, particularly among female students who exhibit heightened dissatisfaction.22 Selen and Koç point out that overweight and obese students exhibit decreased body image perception scores, and that higher internet addiction is associated with a decrease in body aesthetics.23 Yayan and Çelebioğlu report that an obesogenic environment correlates with elevated BMI and decreased body image, whereas social support is associated with increased body satisfaction.24 Doğan et al. observe a significant correlation between body image and sociocultural factors, especially media exposure.25

The results of this study should be interpreted with consideration of several limitations. The study relied solely on self-reported survey data, lacking an impartial evaluation of participants’ psychological well-being, cognitive capacity, or overall health status. No clinical assessment or psychiatric evaluation was conducted, leaving it impossible to elucidate potential underlying mental health issues impacting body perception.

Furthermore, the study lacked a control group or a comparison with a larger population, thereby limiting the generalizability of the findings. The evaluation is cross-sectional, documenting an individual moment rather than assessing changes in self-perception over time. Longitudinal studies may enhance understanding of the interactions between BMI and changes in body image.

Another restriction is that just BMI and body image were compared without considering possible sociocultural influences, peer pressure, or family-related elements that might affect teenagers’ self-image. Future research could combine qualitative techniques, including focus groups or interviews, to obtain a more thorough understanding of the psychological elements of body image perspective.

Moreover, the study focused on a specific age group, and findings may not be applicable to other developmental stages. Expanding the research to different age ranges and socio-economic backgrounds could provide a more comprehensive view of the topic.

CONCLUSION

This study highlights the important relationship between obesity and body image and body satisfaction in school-aged children. Our findings indicate that children with obesity are more likely to experience dissatisfaction with their body image, which may affect their psychological well-being and self-esteem. Conducted using validated tools such as the Children’s Body Image Scale (CBIS) and the Children’s Body Satisfaction Scale (CBSS), this study underscores the importance of incorporating psychosocial dimensions into obesity assessments. Early diagnosis of body image disorders in overweight children can facilitate timely psychological and nutritional interventions. Future long-term studies are needed to investigate the long-term effects of body dissatisfaction on health behaviors and mental health outcomes in this vulnerable population group.

Ethical approval

This study has been approved by the Kartal Dr. Lütfi Kırdar Ethics Committee (approval date 26.03.2025, number 2025/010.99/14/20). Written informed consent was obtained from the participants.

Source of funding

The authors declare the study received no funding.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Bray GA, Kim KK, Wilding JPH, World Obesity Federation. Obesity: a chronic relapsing progressive disease process. A position statement of the World Obesity Federation. Obes Rev. 2017;18:715-23. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12551

- Neumark-Sztainer D, Paxton SJ, Hannan PJ, Haines J, Story M. Does body satisfaction matter? Five-year longitudinal associations between body satisfaction and health behaviors in adolescent females and males. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39:244-51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.12.001

- Smolak L. Body image in children and adolescents: where do we go from here? Body Image. 2004;1:15-28. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1740-1445(03)00008-1

- Truby H, Paxton SJ. Development of the children’s body image scale. Br J Clin Psychol. 2002;41:185-203. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466502163967

- Dohnt H, Tiggemann M. The contribution of peer and media influences to the development of body satisfaction and self-esteem in young girls: a prospective study. Dev Psychol. 2006;42:929-36. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.929

- Tiggemann M. Body dissatisfaction and adolescent self-esteem: prospective findings. Body Image. 2005;2:129-35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2005.03.006

- Latiff AA, Muhamad J, Rahman RA. Body image dissatisfaction and its determinants among young primary-school adolescents. J Taibah Univ Med Sci. 2017;13:34-41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtumed.2017.07.003

- Alberts HJEM, Thewissen R, Raes L. Dealing with problematic eating behaviour. The effects of a mindfulness-based intervention on eating behaviour, food cravings, dichotomous thinking and body image concern. Appetite. 2012;58:847-51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2012.01.009

- Ben-Tovim DI, Walker MK. The development of the Ben-Tovim Walker Body Attitudes Questionnaire (BAQ), a new measure of women’s attitudes towards their own bodies. Psychol Med. 1991;21:775-84. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291700022406

- Grogan S. Body image: understanding body dissatisfaction in men, women and children. Routledge; 2016.

- Neyzi O, Günöz H, Furman A, et al. Türk çocuklarında vücut ağırlığı, boy uzunluğu, baş çevresi ve vücut kitle indeksi referans değerleri. Çocuk Sağ Hast Derg. 2008;51:1-14.

- Keven-Akliman Ç, Özabacı N. Development of the children’s body satisfaction scale: its psychometric characteristics for children. J Paediatr Child Health. 2023;59:298-306. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.16289

- George D, Mallery P. SPSS for Windows step by step: a simple guide and reference 17.0 update. 10th ed. Pearson; 2010.

- Grabe S, Hyde JS. Ethnicity and body dissatisfaction among women in the United States: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2006;132:622-40. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.132.4.622

- Latiff AA, Muhamad J, Rahman RA. Body image dissatisfaction and its determinants among young primary-school adolescents. J Taibah Univ Med Sci. 2017;13:34-41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtumed.2017.07.003

- Hock K, Vanderlee L, White CM, Hammond D. Body weight perceptions among youth from 6 countries and associations with social media use: findings from the international food policy study. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2025;125:24-41.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2024.06.223

- Demaria F, Pontillo M, Di Vincenzo C, Bellantoni D, Pretelli I, Vicari S. Body, image, and digital technology in adolescence and contemporary youth culture. Front Psychol. 2024;15:1445098. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1445098

- Stice E, Shaw HE. Role of body dissatisfaction in the onset and maintenance of eating pathology: a synthesis of research findings. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:985-93. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00488-9

- Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Shafran R. Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: a “transdiagnostic” theory and treatment. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41:509-28. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0005-7967(02)00088-8

- Bearman SK, Martinez E, Stice E, Presnell K. The skinny on body dissatisfaction: a longitudinal study of adolescent girls and boys. J Youth Adolesc. 2006;35:217-29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-005-9010-9

- Groesz LM, Levine MP, Murnen SK. The effect of experimental presentation of thin media images on body satisfaction: a meta-analytic review. Int J Eat Disord. 2002;31:1-16. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.10005

- Ozmen D, Ozmen E, Ergin D, et al. The association of self-esteem, depression and body satisfaction with obesity among Turkish adolescents. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:80. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-7-80

- Selen H, Koç Ş. Evaluation of internet addiction and nutrition habits of secondary and high school students. Bes Diy Derg. 2024;52:58-67. https://doi.org/10.33076/2024.BDD.1832

- Yayan EH, Çelebioğlu A. Effect of an obesogenic environment and health behaviour-related social support on body mass index and body image of adolescents. Glob Health Promot. 2018;25:33-42. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757975916675125

- Dogan O, Bayhan P, Yukselen A, Isitan S. Body image in adolescents and its relationship to socio-cultural factors. Educ Sci Theory Pract. 2018;18:561-77. https://doi.org/10.12738/estp.2018.3.0569

Copyright and license

Copyright © 2025 The author(s). This is an open-access article published by Aydın Pediatric Society under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, provided the original work is properly cited.