Abstract

Objective: To determine whether prolonged colchicine therapy and higher colchicine doses are independently associated with vitamin B12 deficiency in pediatric familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) patients, after adjusting for age as a confounding factor.

Methods: This retrospective study included pediatric FMF patients with biallelic exon 10 MEFV mutations, followed between August 2016 and September 2024. Patients receiving colchicine treatment for at least 12 months and with available serum vitamin B12 measurements were included. Vitamin B12 levels were categorized as deficient (≤200 pg/mL) or normal (>200 pg/mL). Demographic data, colchicine treatment duration and dosage, clinical features, and Pras disease severity scores were recorded.

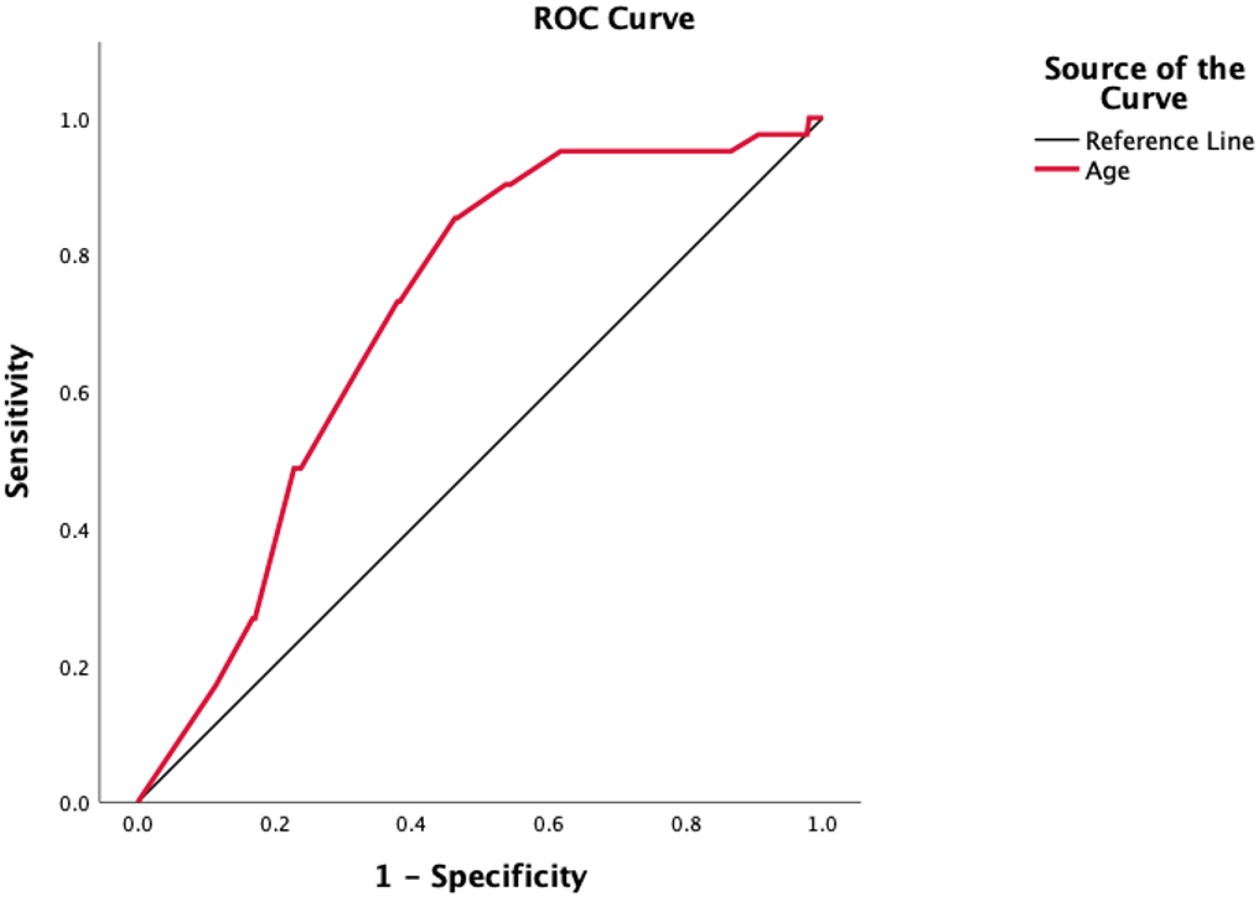

Results: Among 339 patients, 193 (56.9%) were female. The median age at FMF diagnosis was 5 years (interquartile range [IQR], 3-9), and at vitamin B12 testing was 13 years (IQR, 9-16). The median of vitamin B12 levels was 317 pg/mL (236.7-447), and 12.1% of patients had vitamin B12 deficiency. Patients with vitamin B12 deficiency had significantly longer colchicine duration (72 months [48-144] vs. 60 months [24-96], p=0.034) and higher daily colchicine doses (1.33±0.4 vs. 1.12±0.4, p=0.004) compared to those with normal vitamin B12 levels. Patients with a colchicine duration of more than 96 months had the lowest vitamin B12 status (p=0.008) and the highest frequency of vitamin B12 deficiency (p=0.014). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) system analysis identified an age threshold of 12.2 years as predictive for vitamin B12 deficiency (area under the curve=0.708; sensitivity=85.4%; specificity=53.4%). At the time of vitamin B12 measurement, 28 (8.3%) were colchicine-resistant FMF patients, and vitamin B12 deficiency was significantly more common in colchicine-resistant FMF patients compared to colchicine-responsive FMF patients (n=21, 7%) (p=0.03). No significant association was observed between MEFV mutation subtypes (p=0.35), nor between PRAS severity categories (p=0.71) with vitamin B12 status.

Conclusion: Vitamin B12 deficiency appears to be associated with age in pediatric FMF patients. Although prolonged colchicine treatment and higher daily doses were associated with lower B12 levels, these associations were not independent of age. Routine monitoring may be considered in adolescents and with long-standing disease. Further prospective studies are needed to clarify the long-term impact of colchicine on vitamin B12 levels.

Keywords: familial Mediterranean fever, vitamin B12, colchicine, pediatrics, MEFV gene

INTRODUCTION

Familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) is the most common monogenic autoinflammatory disorder of childhood, characterized by recurrent episodes of fever and serositis.1 The disease is caused by autosomal recessive mutations in the Mediterranean fever (MEFV) gene, particularly pathogenic variants located in exon 10, including M694V, M680I, and V726A, which are strongly associated with an earlier disease onset and a more severe disease phenotype.2,3 Colchicine has remained the cornerstone of FMF treatment since its introduction in 1972, effectively preventing inflammatory attacks and significantly reducing the risk of secondary amyloidosis.4 Although generally well tolerated, colchicine could cause gastrointestinal side effects, including abdominal pain, decreased appetite, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.5,6 Due to its anti-mitotic properties, colchicine may also interfere with intestinal absorption, including vitamin B12.5,6

Vitamin B12 (cobalamin) is a water-soluble vitamin essential for hematological function and neurologic development, particularly in pediatric populations.7,8 Experimental data suggest that colchicine may impair vitamin B12 absorption by downregulating intrinsic factor receptors in the terminal ileum and accelerating gastrointestinal transit time.9,10 In addition, disease-related factors, such as MEFV genotype and disease activity, may further influence vitamin B12 status. Patients with more severe clinical phenotypes, particularly those with biallelic exon 10 mutations, often require prolonged or higher-dose colchicine therapy11, which could increase the risk of subtle nutritional deficiencies, including vitamin B12 deficiency. 12

Despite these mechanisms, the relationship between colchicine treatment, FMF genotype, disease severity, and serum vitamin B12 levels remains underexplored, especially in pediatric populations.

In this study, we aimed to determine whether prolonged colchicine therapy and higher colchicine doses are independently associated with vitamin B12 deficiency in pediatric FMF patients with biallelic exon 10 mutations, after adjusting for age as a potential confounder.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This retrospective, single-center study included pediatric patients diagnosed with FMF who carried biallelic MEFV exon 10 mutations and were followed at our referral pediatric rheumatology clinic between August 2016 and September 2024. Eligible patients had a recorded serum vitamin B12 measurement in their medical files and had been receiving colchicine therapy for at least 12 months at the time of assessment.

The diagnosis of FMF was established according to the Eurofever/PRINTO classification criteria13 and/or the Turkish pediatric FMF criteria.14 Based on EULAR (the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology) recommendations, the standard dose of colchicine is 1.2 mg/m2/day, with age-adjusted daily dosing defined as follows: ≤0.5 mg/day for children under 5 years of age, 0.5–1.0 mg/day for children aged 5–10 years, and 1.0–1.5 mg/day for children over 10 years of age.15 Colchicine resistance was defined as experiencing more than one FMF attack per month for at least six months despite receiving the maximum age-appropriate colchicine dosage.16

Exclusion criteria included current or recent usage of vitamin B12 supplementation or proton pump inhibitors; presence of known gastrointestinal malabsorption syndromes (e.g., inflammatory bowel syndrome, celiac disease), or endocrinological diseases; patients on a vegan or vegetarian diet, those with incomplete medical records, or those older than 18 years at the time of vitamin B12 testing.

Demographic and clinical data were collected retrospectively from patient records, including age, sex, disease duration, colchicine dosage, and treatment duration, clinical manifestations, and MEFV gene results. Laboratory parameters included serum vitamin B12 concentrations. Vitamin B12 concentrations were measured using a chemiluminescent immunoassay (ARCHITECT i2000SR, Abbott Diagnostics, Germany), with a reference range of 183–883 pg/mL. All samples were obtained in the fasting state and processed in the same institutional laboratory under standardized protocols. Hemolyzed or lipemic samples were excluded from the analysis. Vitamin B12 deficiency was defined as ≤200 pg/mL and normal as >200 pg/mL, according to international pediatric standards.7 Genetic testing of the MEFV gene was performed using conventional Sanger sequencing and recorded from archived results.

Colchicine treatment duration at the time of vitamin B12 testing was categorized into four groups based on the distribution of treatment lengths: Group 1, 12-24 months; Group 2, 25-60 months; Group 3, 61-96 months; and Group 4, >96 months. Disease severity at the time of B12 testing was assessed retrospectively using the Pras severity score.17,18 Ethical approval was obtained from the local ethics committee (approval date: 10 April 2025, approval number: B.10.1.TKH.4.34.H.GP.0.01/125) and was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) Software version 30.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA). The distribution of numerical variables was assessed using visual methods (histograms) and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov/Shapiro-Wilk tests to assess normality. Descriptive statistics were presented as medians and interquartile ranges (IQR, 25th-75th percentiles) or as means and standard deviations for continuous variables. Categorical variables were presented as numbers and frequencies and compared with the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Prevalence estimates with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated using the bootstrap method. Non-normally distributed continuous numerical data were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test or Kruskal-Wallis test, as appropriate. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed to determine the optimal age cut-off value for predicting vitamin B12 deficiency. The area under the curve (AUC) was calculated to evaluate diagnostic performance, and the optimal threshold was determined using the Youden index, which maximizes the sum of sensitivity and specificity. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test was used as a model-fitting test for binary logistic regression analysis. A two-sided p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

A total of 339 pediatric FMF patients with biallelic MEFV exon 10 mutations and documented serum vitamin B12 levels were included in the study. Of these, 193 patients (56.9%) were female. The median age at symptom onset was 4 years (IQR, 2-7), and at diagnosis was 5 years (IQR, 3-9) (Table 1). The most common genotype was M694V/M694V, followed by M680I/M694V and M694V/V726A.

|

a Values represented as median (interquartile range Q1–Q3) b Values represented as mean ± standard deviation FMF, familial Mediterranean fever; n, number |

|

| Table 1. Characteristics of pediatric patients with FMF | |

|

n = 339 (100%) |

|

| Sex, female, n (%) |

|

| Age at symptom onset, years a |

|

| Age at FMF diagnosis, years a |

|

| Age at vitamin B12 measurement, years a |

|

| Colchicine treatment duration, months a |

|

| Colchicine dose, mg/day b |

|

| Colchicine resistance, n (%) |

|

| Vitamin B12 status, n (%) | |

| Deficient (≤200 pg/mL) |

|

| Normal (>200 pg/mL) |

|

| Serum vitamin B12 level, pg/mL a |

|

| Pras severity score a |

|

| Pras severity category, n (%) | |

| Mild |

|

| Moderate |

|

| Severe |

|

| MEFV mutations | |

| Homozygous M694V |

|

| Compound heterozygous M694V |

|

| Non-M694V compound heterozygote |

|

At the time of vitamin B12 measurement, the median age was 13 years (IQR, 9-16), and 41 patients (12.1% [95% CI: 8.6–15.6]) had B12 deficiency. The median duration of colchicine treatment prior to vitamin B12 measurement was 60 months (IQR 24-96), and the mean colchicine dose at the time of testing was 1.15±0.4 mg/day (Table 1).

Patients with vitamin B12 deficiency had both significantly longer duration and higher daily dosage of colchicine exposure compared to those with normal B12 levels (p=0.034 and p=0.004, respectively) (Table 2). Patients in the longer colchicine treatment duration groups had higher frequencies of vitamin B12 deficiencies (p=0.014) and lower median vitamin B12 levels (p=0.008), suggesting a potential inverse relationship between colchicine exposure and vitamin B12 levels (Table 3). Regarding serum vitamin B12 levels, Group 4 had significantly lower values compared to Group 1 (p=0.004) and Group 2 (p=0.006).

|

a Values represented as median (interquartile range Q1–Q3) b Values represented as mean ± standard deviation FMF, familial Mediterranean fever; n, number |

|||

| Table 2. Comparison of FMF patients with vitamin B12 deficiency and normal vitamin B12 levels | |||

|

n = 41 (12.1%) |

n = 298 (87.9%) |

|

|

| Sex, female, n (%) |

|

|

|

| Age at symptom onset, years a |

|

|

|

| Age at FMF diagnosis, years a |

|

|

|

| Age at vitamin B12 measurement, years a |

|

|

|

| Colchicine treatment duration, months a |

|

|

|

| Colchicine dose, mg/day b |

|

|

|

| Colchicine resistance, n (%) |

|

|

|

| Pras severity score a |

|

|

|

| Pras severity category, n (%) | |||

| Mild |

|

|

|

| Moderate |

|

|

|

| Severe |

|

|

|

| MEFV mutations | |||

| Homozygous M694V |

|

|

|

| Compound heterozygous M694V |

|

|

|

| Non-M694V compound heterozygote |

|

|

|

|

a Values represented as median (interquartile range Q1–Q3) * Post hoc pairwise comparisons using Mann–Whitney U tests with Bonferroni correction (adjusted significance threshold p < 0.0083) showed statistically significant differences in age between Group 4 and Groups 1–3 (all p < 0.001) and between Group 1 and Group 3 (p < 0.001). **Post hoc pairwise comparisons using Mann–Whitney U tests with Bonferroni correction (adjusted significance threshold p < 0.0083) showed statistically significant differences in serum vitamin B12 levels between Group 4 and Group 1 (p = 0.004) and between Group 4 and Group 2 (p = 0.006). FMF, familial Mediterranean fever; IQR, interquartile range; n, number |

|||||

| Table 3. Vitamin B12 status and levels according to duration of colchicine therapy in pediatric FMF patients | |||||

|

12-24 months n=87, 25.7% |

25-60 months n=70, 20.6% |

61-96 months n=87, 25.7% |

>96 months n=90, 28% |

|

|

| Age at vitamin B12 measurement, years a |

|

|

|

|

|

| Vitamin B12 deficiency, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Serum Vitamin B12 level, pg/mL a |

|

|

|

|

|

Vitamin B12 deficiency was significantly more common among patients receiving more than 1 mg/day compared to those receiving 1 mg/day or less (19.1% vs. 8.7%) (p=0.006). Patients receiving more than 1 mg/day (n=229, 67.6%, 331 pg/mL [IQR, 258-452.5]) had significantly lower serum vitamin B12 levels compared to those receiving 1 mg/day or less (n=110, 32.4%, 278 pg/mL [IQR, 217-396.5]) (p<0.001).

Neither median vitamin B12 levels nor the frequency of vitamin B12 deficiency differed significantly by M694V mutation status (p=0.179 and p=0.35, respectively) (Table 2). The median serum B12 levels did not differ significantly among Pras severity groups (p=0.97), and no association was found between Pras severity and vitamin B12 status (p=0.71) (Table 2).

Twenty-eight patients (8.3%) were classified as colchicine-resistant at the time of vitamin B12 measurement, and were receiving anti-interleukin-1 therapy, with a median biologic treatment duration of 22.5 months (IQR, 9.3-31.7) (Table 4). Colchicine-resistant patients were significantly older at the time of vitamin B12 measurement (p<0.001), had significantly longer colchicine exposure (p<0.001), and received a higher daily dose (p<0.001). Vitamin B12 deficiency was more frequent among colchicine-resistant patients compared to the colchicine-responsive group (p=0.03). Although the median serum vitamin B12 level appeared lower in the colchicine-resistant group, this difference did not reach statistical significance (p=0.053) (Table 4).

|

a Values represented as median (interquartile range Q1–Q3) b Values represented as mean ± standard deviation FMF, familial Mediterranean fever; n, number |

|||

| Table 4. Comparison of demographic characteristics and vitamin B12 levels between colchicine-responsive and colchicine-resistant pediatric FMF patients | |||

|

n=311 (91.7%) |

n=28 (8.3%) |

|

|

| Sex, female, n (%) |

|

|

|

| Age at symptom onset, years a |

|

|

|

| Age at FMF diagnosis, years a |

|

|

|

| Age at vitamin B12 measurement, years a |

|

|

|

| Colchicine treatment duration, months a |

|

|

|

| Colchicine dose, mg/day b |

|

|

|

| Anti-IL-1 therapy duration, months a |

|

|

|

| Vitamin B12 deficiency, n (%) |

|

|

|

| Serum vitamin B12 level, pg/mL a |

|

|

|

A significant inverse correlation was observed between age and vitamin B12 levels (Spearman’s ρ = –0.366, p < 0.001), indicating that older patients tended to have lower B12 concentrations. Age also correlated positively with the colchicine treatment duration (Spearman’s ρ=0.514, p<0.001), suggesting that age-related decline in B12 levels may be partially mediated by longer cumulative colchicine exposure over time.

In univariate logistic regression analysis, age (p<0.001), colchicine dose (p=0.005), and colchicine resistance (p=0.035) were significantly associated with vitamin B12 deficiency. However, in multivariate analysis, only age remained a significant predictor (p<0.001), while the associations with colchicine dose (p=0.41), colchicine duration (p=0.47), and colchicine resistance (p=0.25) were no longer significant (Table 5). Model fit was assessed using the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test, which indicated an adequate fit (χ²=5.54, p=0.69). ROC analysis revealed that an age threshold of 12.2 years best predicted vitamin B12 deficiency, with an AUC of 0.708 (standard error: 0.037; 95% CI: 0.635-0.780; p<0.001), yielding a sensitivity of 85.4% and specificity of 53.4% (Figure 1).

|

Hosmer-Lemeshow test chi-square = 5.54, p = 0.69 CI, confidence interval; FMF, familial Mediterranean fever; OR, odds ratio |

||||

| Table 5. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis for predictors of vitamin B12 deficiency in pediatric FMF patients | ||||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Age |

|

|

|

|

| Colchicine Dose |

|

|

|

|

| Colchicine Duration |

|

|

|

|

| Colchicine Resistance |

|

|

|

|

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective study, we evaluated serum vitamin B12 concentrations in pediatric patients with FMF carrying biallelic exon 10 mutations, along with clinical and genetic variables, including colchicine treatment duration, disease severity, and MEFV variants. Our findings indicate that vitamin B12 deficiency is relatively common, 12.1%, among children with FMF, and that older age (>12.2 years) emerged as an independent risk factor for reduced vitamin B12 levels.

Colchicine remains the mainstay of FMF treatment. However, its side effect profile primarily involves gastrointestinal symptoms, including diarrhea, abdominal pain, and vomiting.5,6 In literature, it has been suggested that long-term and high-dose colchicine therapy may impair vitamin B12 absorption by altering intestinal motility and inhibiting the function of intrinsic factor-B12 receptors in the terminal ileum.5-7 Our findings are consistent with these proposed mechanisms, as we observed a statistically significant decrease in vitamin B12 levels among patients with longer colchicine treatment duration (>96 months). In a study by Yılmaz et al.19, a significant reduction in mean serum vitamin B12 levels, from 418 pg/ml to 240 pg/ml, was observed after the initiation of colchicine therapy within 16.5±9.8 months, which concluded that administration of colchicine may lead to a reduction in vitamin B12 levels.

In our FMF cohort, the frequency of vitamin B12 deficiency was 12.1% (95% Cl: 8.6–15.6), which appears higher than the reported prevalence of 5.5% in a large cohort of 3,163 healthy children from the same country.20 Previous studies have reported conflicting results regarding the impact of colchicine on vitamin B12 levels. Gemici et al.21 reported significantly lower vitamin B12 levels in FMF patients compared with the healthy control group, suggesting a colchicine-related effect. Conversely, Başaran et al.22 found no relationship between colchicine duration and vitamin B12 levels but observed lower vitamin B12 levels in patients receiving higher colchicine doses (>1 mg/day). In our study, we demonstrated that both longer duration (>96 months) and higher daily colchicine doses (>1 mg/day) were independently associated with lower serum vitamin B12 levels, supporting a dose-dependent impact on vitamin B12 metabolism or absorption. However, these associations did not remain significant after adjusting for age. Multivariate analysis models suggest that the effects of colchicine-related variables may be confounded by age, as older patients are more likely to receive longer treatment durations.

While the majority of our cohort carried at least one M694V mutation, no statistically significant differences in vitamin B12 levels were observed when stratified by mutation status. These results suggest that M694V mutation status alone does not appear to affect serum B12 concentrations. This finding supports that colchicine-related factors, such as dose and duration, rather than genotype itself, may play a more prominent role in reducing vitamin B12 status.

Despite our hypothesis that greater disease severity would correlate with lower vitamin B12 levels due to chronic inflammation, no significant relationship was found between the Pras severity score and vitamin B12 concentrations. This may, in part, reflect the limitations of cross-sectional severity indices in reflecting cumulative disease burden. Similarly, in a study by Tetik Dincer et al.23, vitamin B12 levels were not affected by attack frequency, suggesting that attack frequency alone may be insufficient to reflect disease activity.

Notably, colchicine-resistant FMF patients in our study had a significantly higher prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency than colchicine-responsive patients. However, this group also had older age and longer colchicine treatment duration, which may confound the observed association. These findings highlight the multifactorial nature of vitamin B12 status in FMF and suggest that disease severity score or colchicine response alone may not adequately reflect risk for subclinical micronutrient deficiencies. Identifying and correcting vitamin B12 deficiency in this subgroup could help prevent additive complications such as anemia, fatigue, or impaired growth, and may improve overall disease management and quality of life.

Our findings suggest that FMF patients older than 12.2 years of age and those under long-term colchicine therapy (>96 months) may be at increased risk of vitamin B12 deficiency, regardless of specific MEFV variants. The observed association between prolonged colchicine therapy and lower vitamin B12 levels may, in part, reflect increasing patient age as both variables are closely linked. Furthermore, our multivariate logistic regression analysis confirmed that age was the main independent predictor of vitamin B12 deficiency. In addition, vitamin B12 deficiency appeared to be more frequent in adolescents with FMF than in healthy pediatric populations.20,23 The finding that age emerged as the only independent predictor of vitamin B12 deficiency may be explained by biological plausibility. During adolescence, rapid growth, pubertal changes, and dietary shifts increase the metabolic demand for vitamin B12 and may alter its absorption20, potentially confounding the association with treatment-related factors. In addition, in FMF patients, prolonged colchicine exposure during these critical developmental years may further contribute to the risk of deficiency, highlighting the combined effect of age and long-term therapy. Based on the analyses, our findings indicate that the prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency may warrant routine screening in FMF patients during adolescence, particularly among those receiving long-term colchicine therapy. Such an approach could facilitate early recognition and timely management of deficiency in this vulnerable subgroup.

Our study has several strengths, including a large cohort, exclusion of potential confounders such as vitamin B12 supplementation and comorbid malabsorption conditions, and detailed stratification by genotype and disease severity. However, this study has several limitations. Due to its retrospective design, data on patients’ nutritional status, dietary vitamin B12 intake, and pubertal stage were lacking, and baseline vitamin B12 measurements before colchicine initiation were not available. Moreover, the lack of a healthy control group limits direct comparison of vitamin B12 levels between FMF patients and the healthy pediatric population. Further prospective studies comparing vitamin B12 levels with other vitamin levels and dietary intake of vitamins could be more important. Longitudinal assessments of vitamin B12 levels before initiation and after long-term colchicine treatment would provide further understanding of the specific impact of treatment over time.

In conclusion, this study underscores the potential for vitamin B12 deficiency in pediatric FMF patients, particularly in adolescent patients. While those receiving long-term (>96 months), higher dose (>1 mg/day) colchicine therapy, or colchicine resistance appeared to be associated with lower vitamin B12 levels, age was the independent predictor of vitamin B12 deficiency. Further prospective studies are warranted to better elucidate the long-term impact of colchicine on vitamin B12 metabolism and to determine whether routine screening should be recommended for all pediatric FMF patients undergoing colchicine treatment.

Ethical approval

This study has been approved by the Umraniye Traning and Research Hospital, University of Health Sciences Ethics Committee (approval date 10.04.2025, number B.10.1.TKH.4.34.H.GP.0.01/125).

Source of funding

The authors declare the study received no funding.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Lancieri M, Bustaffa M, Palmeri S, et al. An update on familial mediterranean fever. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:9584. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24119584

- Ayaz NA, Tanatar A, Karadağ ŞG, Çakan M, Keskindemirci G, Sönmez HE. Comorbidities and phenotype-genotype correlation in children with familial Mediterranean fever. Rheumatol Int. 2021;41:113-20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-020-04592-7

- Tunce E, Atamyıldız Uçar S, Polat MC, et al. Predicting homozygous M694V genotype in paediatric FMF: multicentre analysis and scoring system proposal. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2025;64:4816-24. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keaf221

- Batu ED, Basaran O, Bilginer Y, Ozen S. Familial mediterranean fever: how to interpret genetic results? How to treat? A quarter of a century after the association with the mefv gene. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2022;24:206-12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-022-01073-7

- Stamp LK, Horsley C, Te Karu L, Dalbeth N, Barclay M. Colchicine: the good, the bad, the ugly and how to minimize the risks. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2024;63:936-44. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kead625

- Webb DI, Chodos RB, Mahar CQ, Faloon WW. Mechanism of vitamin B12 malabsorption in patients receiving colchicine. N Engl J Med. 1968;279:845-50. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM196810172791602

- Green R, Miller JW. Vitamin B12 deficiency. Vitam Horm. 2022;119:405-39. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.vh.2022.02.003

- Rasmussen SA, Fernhoff PM, Scanlon KS. Vitamin B12 deficiency in children and adolescents. J Pediatr. 2001;138:10-7. https://doi.org/10.1067/mpd.2001.112160

- Demir A, Akyüz F, Göktürk S, et al. Small bowel mucosal damage in familial Mediterranean fever: results of capsule endoscopy screening. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:1414-8. https://doi.org/10.3109/00365521.2014.976838

- Mansueto P, Seidita A, Chiavetta M, et al. Familial mediterranean fever and diet: a narrative review of the scientific literature. Nutrients. 2022;14:3216. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14153216

- Tunce E, Uçar SA, Coşkuner T, et al. Preliminary evaluation for the development of a scoring system to predict homozygous M694V genotype in familial mediterranean fever patients: a single-center study. J Clin Rheumatol. 2025;31:7-11. https://doi.org/10.1097/RHU.0000000000002165

- Ekinci RMK, Balci S, Serbes M, Dogruel D, Altintas DU, Yilmaz M. Decreased serum vitamin B12 and vitamin D levels affect sleep quality in children with familial Mediterranean fever. Rheumatol Int. 2018;38:83-7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-017-3883-2

- Gattorno M, Hofer M, Federici S, et al. Classification criteria for autoinflammatory recurrent fevers. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:1025-32. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215048

- Yalçinkaya F, Ozen S, Ozçakar ZB, et al. A new set of criteria for the diagnosis of familial Mediterranean fever in childhood. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009;48:395-8. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/ken509

- Ozen S, Demirkaya E, Erer B, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of familial Mediterranean fever. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:644-51. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208690

- Ozen S, Kone-Paut I, Gül A. Colchicine resistance and intolerance in familial mediterranean fever: Definition, causes, and alternative treatments. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2017;47:115-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2017.03.006

- Pras E, Livneh A, Balow JE, et al. Clinical differences between North African and Iraqi Jews with familial Mediterranean fever. Am J Med Genet. 1998;75:216-9. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19980113)75

- Ozen S, Aktay N, Lainka E, Duzova A, Bakkaloglu A, Kallinich T. Disease severity in children and adolescents with familial Mediterranean fever: a comparative study to explore environmental effects on a monogenic disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:246-8. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2008.092031

- Yilmaz R, Ozer S, Ozyurt H, Erkorkmaz U. Serum vitamin B12 status in children with familial mediterranean fever receiving colchicine treatment. HK J Paediatr. 2011;16:3-8.

- Kara İS, Peker NA, Dolğun İ, Mertoğlu C. Vitamin B12 level in children. J Curr Pediatr. 2023;21:127-34. https://doi.org/10.4274/jcp.2023.75688

- Gemici AI, Sevindik ÖG, Akar S, Tunca M. Vitamin B12 levels in familial Mediterranean fever patients treated with colchicine. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2013;31:57-9.

- Başaran Ö, Uncu N. Kolşisin tedavisi altındaki ailevi akdeniz ateşi tanısı ile takip edilen çocuk hastalarda vitamin B12 düzeylerinin değerlendirilmesi. Güncel Pediatri. 2018;16:86-92. https://doi.org/10.4274/jcp.2018.0023

- Tetik Dincer B, Ozcelik G, Urganci N. Comparison of vitamin D, B12, and folic acid levels according to attack frequency in familial mediterranean fever cases. Sisli Etfal Hastan Tip Bul. 2024;58:359-62. https://doi.org/10.14744/SEMB.2024.86461

Copyright and license

Copyright © 2025 The author(s). This is an open-access article published by Aydın Pediatric Society under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, provided the original work is properly cited.