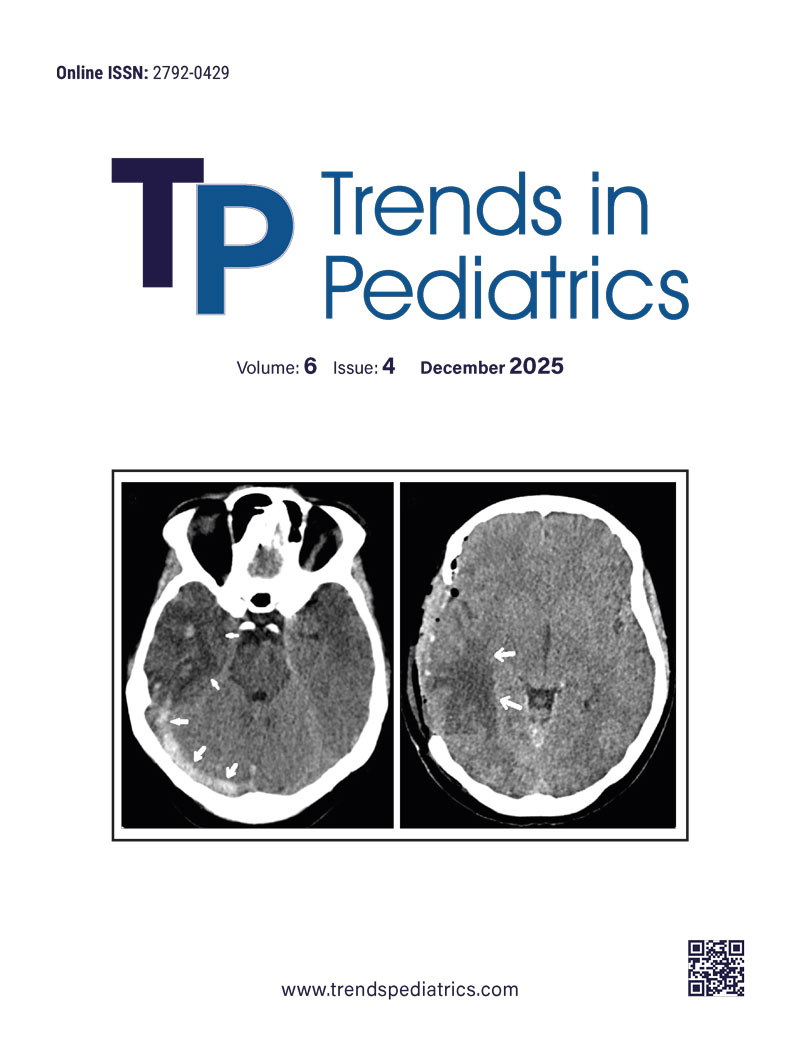

Abstract

Diagnosing abdominal tuberculosis (TB) is challenging due to its uncommon symptoms and limited diagnostic tools, which can delay treatment and increase mortality. We present two cases of abdominal TB diagnosed using different approaches. In case 1, a 6-year-old girl with a month-long history of ascites, whose father had treatment-resistant TB, was evaluated. The tuberculin test was positive, but the Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra assay was negative. Laparoscopy revealed miliary nodules, and histopathology confirmed the presence of granulomas with Langhans giant cells. In case 2, a 1-year-old girl presented with seven months of ascites and no known TB contact. The tuberculin test was negative, but an abdominal CT scan showed hepatic TB. The in-house polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for TB targeting the IS3-like element IS987 family transposase in our laboratory was positive. Both patients were diagnosed with abdominal TB, treated with the extrapulmonary (EPTB) regimen, and showed significant improvement. Diagnosing abdominal TB is complex, requiring a thorough history and adequate examination support. This might prevent delays in treatment that potentially increase complications.

Keywords: abdominal tuberculosis, children, diagnosis, histopathology, PCR

INTRODUCTION

Tuberculosis (TB) is a chronic infectious disease that remains a worldwide health issue.1 It affects more than 70 million children aged 0 to 14 years, resulting in an estimated 230,000 deaths, which positions it among the top 10 leading causes of death. In Indonesia, pediatric TB accounts for about 12% of all TB cases, which translates to over 80,000 instances.1,2

Abdominal TB, as an extrapulmonary manifestation, is rare but serious and can affect various abdominal structures, including the gastrointestinal tract, peritoneum, abdominal solid organs, and lymphatic drainage.3 In China, 14.55% of 2,130 children with EPTB had abdominal TB, making it the fourth most common type of EPTB after meningitis, pleurisy, and lymphatic TB.4 Symptoms like abdominal discomfort, distention, ascites, diarrhea, vomiting, and pain are common, but these do not always lead directly to a diagnosis of TB without strong clinical evidence.3,5 The nonspecific presentation can also mimic other conditions, such as inflammatory diseases, malignancies, or intestinal perforation, leading to a delay in diagnosis or could evoke unnecessary surgery.5 Moreover, the absence of clear recommendations for diagnostic tools for abdominal TB complicates the diagnosis, particularly in resource-limited settings.6

In this report, we highlight two cases of pediatric abdominal TB diagnosed at our tertiary hospital. These cases illustrate the complexities of diagnosing, underscoring the importance of a comprehensive diagnostic approach and thorough clinical examination. They also emphasize the significance of timely and efficient treatment to prevent severe complications linked to abdominal TB.

Case Presentation

Case 1

A 6-year-old girl was admitted with abdominal distension and discomfort lasting for one month. She had no history of fever, cough, night sweats, or weight loss. Her father, diagnosed with bacteriologically confirmed pulmonary TB (PTB) eight months before her symptoms began, was undergoing treatment for TB, which had been deemed a failure. The girl had not received the Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccine.

Her current clinical status was within normal limits; however, anthropometry indicated undernutrition, with mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) at 76% of the standard reference value. The abdomen was distended (abdominal circumference: 62 cm), with positive bowel sounds, undulation, and shifting dullness. The laboratory findings indicated mild anemia, with a hemoglobin (HGB) level of 10.70 g/dL and a mean corpuscular volume (MCV) of 75.50 fL. Other laboratory tests, including liver function tests, were within normal limits.

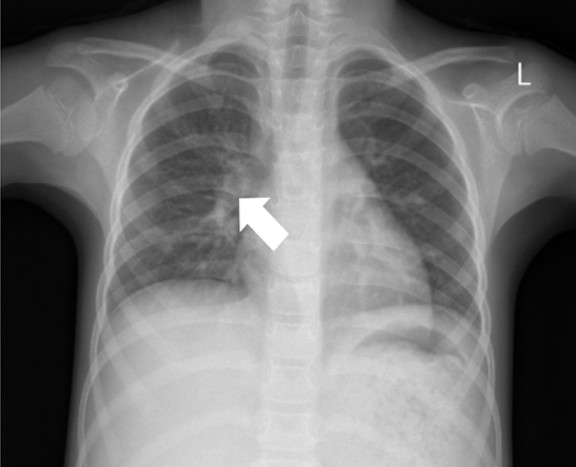

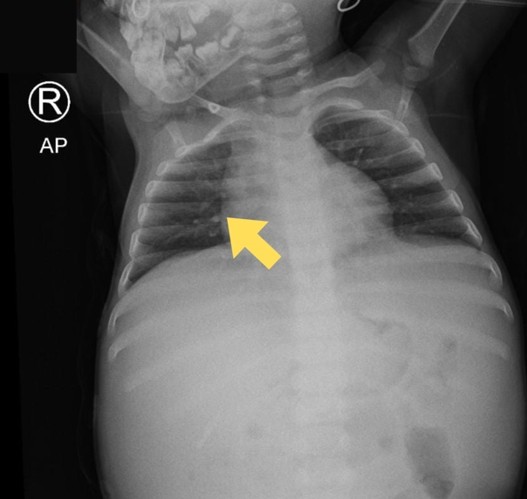

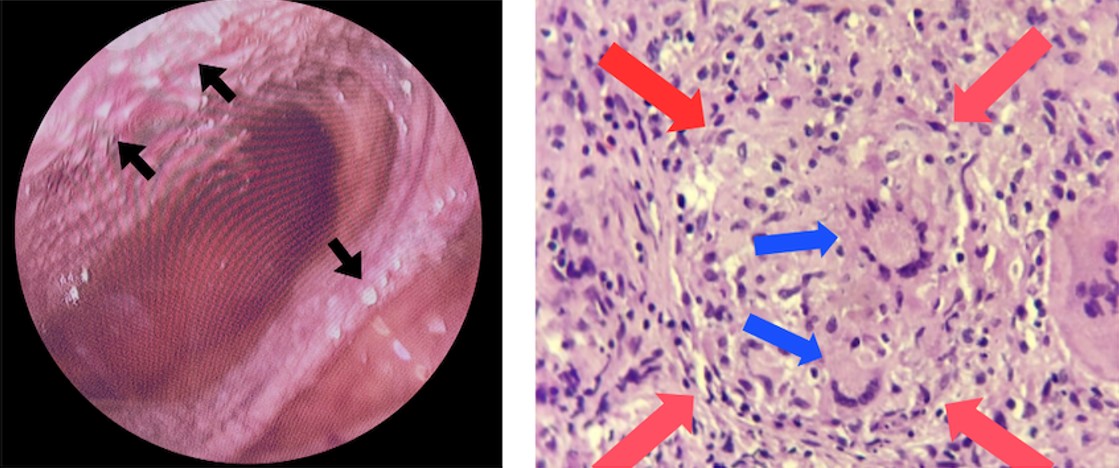

The abdominal X-ray showed distension and a sentinel loop in the left upper quadrant (Figure 1A), while the ultrasound revealed ascites (Figure 1B). The MTB/RIF Ultra (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, California, USA) test on sputum was negative, but a positive tuberculin test showed a 20 mm induration. A chest X-ray revealed hilar lymphadenopathy (Figure 2), giving a TB score of eight. Subsequently, to assess for extrapulmonary TB (EPTB), an ascitic fluid sample was obtained via laparoscopic examination. During the procedure, multiple whitish tubercles were observed (Figure 3A). Although the MTB/RIF Ultra test of the fluid was negative, the adenosine deaminase (ADA) level was elevated at 58 U/L, and histopathology confirmed abdominal TB with epithelioid granulomas and Langhans giant cells (Figure 3B). The HIV test was nonreactive.

She started the intensive phase of anti-tuberculosis therapy (ATT) with four tablets of a pediatric fixed-dose combination of Rifampicin (R), Isoniazid (H), Pyrazinamide (Z) (75/50/150), and Ethambutol (20 mg/kg/day). She followed the 6-month therapy following national guidelines, and showed clinical improvement, including a 20% reduction in abdominal circumference (to 50 cm) and an increase in MUAC (from 76% to 79%), with no gastrointestinal or respiratory issues.

Case 2

A 1-year-old girl was referred to our tertiary hospital from X Province Hospital with a primary complaint of ascites that had persisted for seven months. She also had a persistent fever and cough for three months. Significant weight loss was noted three months before admission to X Hospital. The patient’s family and close contacts had no known history of tuberculosis exposure. Her immunization was completed.

She was previously diagnosed with sepsis caused by Gamella morbillorum, massive ascites, and clinically suspected PTB. She had been treated at the previous hospital for about one month with the following regimen: vancomycin for 12 days, a single-drug ATT for 19 days, and prednisone for 18 days. However, the ascites did not improve.

Her vital signs were within normal limits, but the anthropometric assessment indicated undernourishment (MUAC 76%). The abdominal examination showed distention (60 cm) with distant bowel sounds. The ascites drainage inserted at the previous hospital was well-placed, aiding in the removal of excess fluid. The tuberculin skin test showed an 8 mm induration, and the chest radiograph from the previous hospital showed hilar right lymphadenopathy (Figure 4). The MTB/RIF Ultra from gastric lavage was negative.

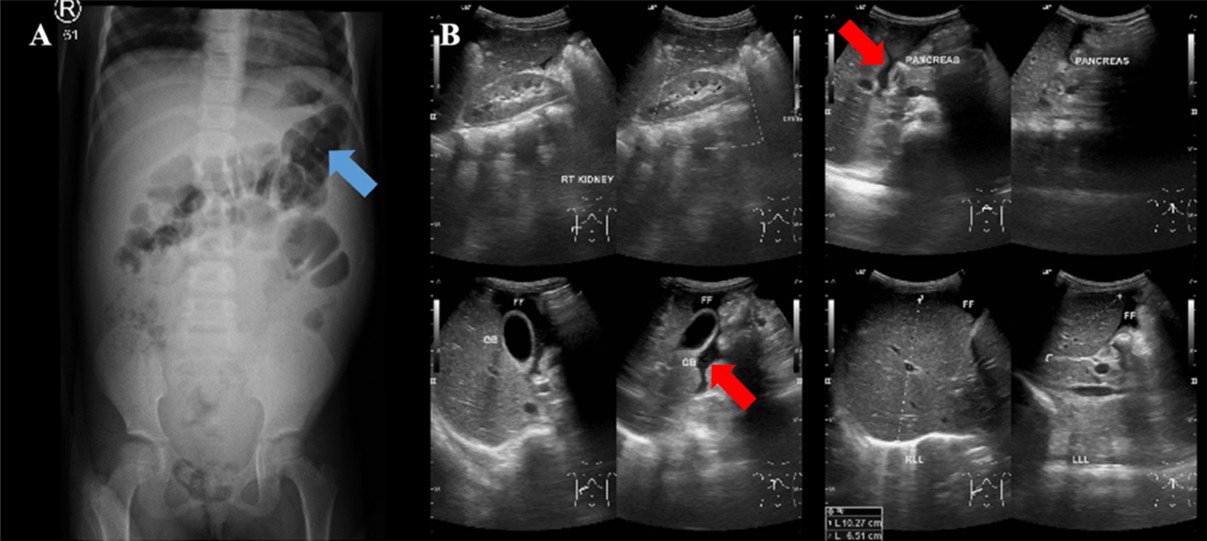

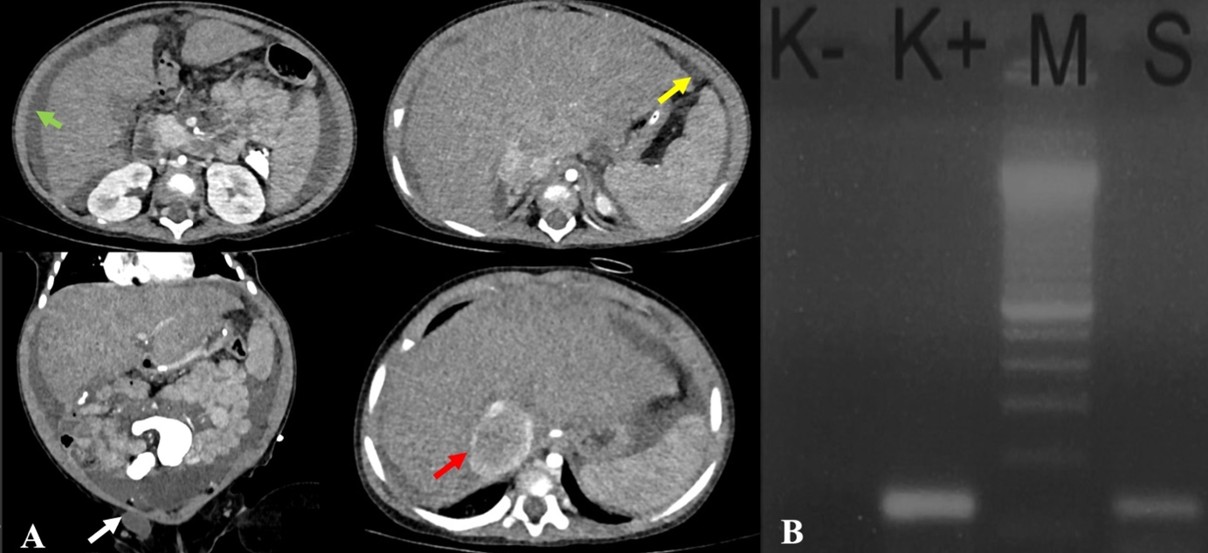

The laboratory results showed microcytic hypochromic anemia with an HGB of 10.00 g/dL and MCV of 65.20 fL. The liver function, bilirubin, and septic markers were normal. An earlier abdominal ultrasound revealed massive ascites. An abdominal CT with contrast revealed ascites in the abdominal and pelvic cavities, dilatation of the inferior vena cava (IVC) due to thrombus formation, a hypodense lesion with peripheral enhancement in the hepatic parenchyma, minimal nodular peritoneal thickening, and reactive lymph nodes in the inguinal regions, suggesting abdominal (hepatic) TB (Figure 5A).

Ascitic fluid analysis revealed a serum-ascites albumin gradient (SAAG) of 1.5 g/dL (transudate). Subsequently, the MTB/RIF Ultra was negative, and the ADA was 20 U/L. Given the inconclusive findings, we opted for in-house polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing of the ascitic fluid rather than laparoscopy due to the significant ascites. The primers and target gene used for the PCR were provided by our Clinical Microbiology Laboratory, as follows: PCR TB E1 (5′-CCTGCGAGCGTAGGCGTC) and PCR TB E2 (5′-CCGTCCAGCGCCGCTGTCGG), targeting the IS3-like element IS987 family transposase. DNA extraction was performed using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit, and amplification was carried out with a T100 Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad) using GoTaq Green Master Mix. The ascitic fluid sample tested positive for TB by PCR, thereby confirming the diagnosis of abdominal TB. The patient completed the intensive phase of ATT with two pediatric fixed-dose combination RHZE tablets once daily for 2 months and entered the continuation phase. (Figure 5B).

The antibiotic treatment was stopped upon admission to our hospital due to minimal signs of bacterial infection. Abdominal circumference reduced by 11.6% and MUAC increased by 78.8% within 2 weeks of treatment.

The patient’s parents gave their consent for these cases to be published for academic purposes, with the assurance that their identities would remain confidential. Ethical approval was granted by our institution’s ethics committee.

Discussion

Abdominal TB in children is a rare but significant form of EPTB, presenting with diagnostic and management challenges due to its atypical presentation and potential for severe complications.7 Based on anamnesis and physical examination, abdominal TB was suspected in Case 1 due to distention and a history of contact with PTB, while in Case 2, it was suspected because of distention, fever, cough, and weight loss. In both cases, malnutrition and anemia may also support a chronic infection.

Contacts of TB patients are at increased risk of acquiring either PTB or EPTB.8 A study in Pakistan found a family history of TB significantly associated with EPTB, especially in children aged 0-4 years.9 Additionally, a previous study in Bali stated that an incomplete BCG history is associated with a threefold higher risk of developing EPTB.10 Although no studies have explored the association between failed TB treatment in adults and EPTB in children, it is likely that the abdominal TB in Case 1 was related to her father’s PTB as the index case, along with an incomplete BCG vaccination history.

Following initial suspicion, TST usually shows increased induration, indicating TB infection. A study in Turkey found a 69.2% TST positivity rate among children with abdominal TB.11 In Case 1, a 20 mm induration was observed, which typically indicates TB infection. In contrast, in Case 2, an 8 mm induration was noted, which was considered doubtful given the patient’s negative immunosuppressive status. Therefore, while the TST can raise suspicion, it must be interpreted in conjunction with other diagnostic tools for a more accurate diagnosis.12

Recent national guidelines for TB in children recommend ruling out PTB if EPTB is suspected.13 This might indicate an infectious source of initial involvement in the development of abdominal TB. Both cases showed negative MTB/RIF Ultra results from sputum or gastric aspirate. However, chest X-rays revealed right hilar lymphadenopathy, which is a common radiological hallmark of primary TB in children, seen in 50-70% of cases.14

The abdominal CT is preferred for detailed visualization, revealing inflammation in abdominal structures and differentiating between TB-related ascites and cancer.15 Abdominal CT can also show peritoneal or intestinal wall thickening, a key feature of abdominal TB.5,16 In a case series in Turkey, the most common findings in abdominal CT were lymphadenopathy, peritoneal thickening, ascites, hepatosplenomegaly, and multiple nodules.11 In Case 2, there was a hypodense lesion with peripheral enhancement in the hepatic parenchyma and minimal nodular peritoneal thickening, which aligns with hepatic TB features.

Molecular testing, including ascitic fluid examination, acid-fast bacilli (AFB) staining, MTB/RIF, and PCR, is crucial in diagnosing abdominal TB. In peritoneal TB, ascitic fluid typically has SAAG < 1.1 g/dL, while SAAG > 1.1 g/dL is commonly seen in patients with cirrhosis or inferior vena cava (IVC) obstruction.17 In Case 2, ascitic fluid analysis revealed a SAAG > 1.1 g/dL, correlating with abdominal CT findings that suggested IVC obstruction as the cause of the transudate pattern. The association between IVC obstruction and abdominal TB is rarely reported, but it may result from acquired IVC thrombosis caused by external compression from swollen retroperitoneal lymph nodes, which distort the IVC and promote thrombus formation.18,19 Consequently, we closely monitored homeostatic function (INR at 1.2) and signs of obstruction.

The MTB/RIF Ultra, introduced by the WHO in 2017, is claimed to have higher sensitivity than the previous version, as it includes two distinct multi-copy amplification targets (IS6110 and IS1081) and has a larger DNA reaction chamber compared to Xpert MTB/RIF.20 In a study conducted by Slail et al.,21 the sensitivity and specificity of Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra from ascitic fluid were 75% and 93%, respectively, with a positive predictive value (PPV) of 60% and a negative predictive value (NPV) of 96%.21 However, in these cases, the MTB/RIF Ultra results from ascitic fluid were negative. The recent WHO guidelines conditionally recommend Xpert MTB/RIF and Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra as initial diagnostic tests, due to low certainty in peritoneal fluid specimens.22

The ADA test has been reported to be highly effective in diagnosing abdominal TB.23 A recent meta-analysis by Mahajan et al.24 in 2023 reported a pooled sensitivity of 90% and specificity of 94% for the ADA test compared with bacteriologically confirmed M. tuberculosis or histopathology. The study also found that a cut-off value above 30 U/L resulted in an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.95.24 Both patients underwent the ADA test, with Case 1 showing a higher level (58 U/L). In contrast, Case 2 had an ADA level of 20 U/L, which was not indicative of abdominal TB. This could be due to early-stage abdominal TB or the patient’s immunocompromised state from sepsis.23

The PCR testing for M. tuberculosis DNA is a highly sensitive and specific method, with a specificity of 96-99%, making it valuable in diagnosing TB when traditional methods fall short.25 In Case 2, the positive PCR result was crucial in confirming the abdominal TB diagnosis, despite the weak Mantoux test reaction. Histopathology is another key diagnostic tool, often serving as the reference standard when culture results are limited.26 Caseating granulomas, characterized by central necrosis surrounded by epithelioid cells, Langhans giant cells, and infiltrating lymphocytes, are typically present in TB.27 In Case 1, histopathological examination confirmed these granulomas and Langhans giant cells, reinforcing the diagnosis of abdominal TB. However, microbiological confirmation could not be established in this case, as AFB staining and mycobacterial culture were not performed.

The AFB staining was not performed in our diagnostic work-up because, according to the current national tuberculosis guidelines, this method has low sensitivity.13 Therefore, AFB staining is no longer recommended as the primary bacteriological diagnostic tool for tuberculosis.13 Mycobacterial culture, although still considered the gold standard, was also not performed in these cases due to its lengthy turnaround time and its frequent negative results, particularly in paucibacillary forms of the disease.5 Because of these limitations, we combined several diagnostic modalities—including imaging and molecular tests (Xpert MTB/RIF, PCR), ADA testing, and histopathological examination—to achieve a more comprehensive and reliable diagnosis.

Finally, the diagnosis of abdominal TB in both patients was confirmed through several examinations (Table 1). Following national guidelines for EPTB treatment, anti-tuberculosis therapy (ATT) was promptly initiated. Both patients demonstrated a satisfactory treatment response, including a reduction in abdominal circumference and weight gain, confirming that the diagnosis was consistent with the positive treatment outcomes.

| PTB, pulmonary tuberculosis; TST, tuberculin skin test; BCG, bacilli Calmette–Guérin; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; CT, computed tomography; SAAG, serum-ascites-albumin-gradient; ADA, adenosine deaminase; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; TB, tuberculosis; RHZE, rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol; RH, rifampicin and isoniazid; FDC, fixed dose combination; OD, once daily; N/A, not available. | ||

| Table 1. The different diagnostic approaches in both cases | ||

| Case 1 | Case 2 | |

| Gender | Girl | Girl |

| Age (years) | 6 | 1 |

| Body weight | 20 kg | 9.5 kg |

| Signs and symptoms | Abdominal distention | Abdominal distention, fever > 2 weeks, cough > 2 weeks, decrease in body weight |

| Contact history | Father with PTB on treatment | Not known |

| BCG vaccination | No | Yes, scar (+) |

| TST | Positive (≥ 10 mm) | <10 mm |

| HIV examination | Negative | Negative |

| Sputum and/or Gastric lavage MTB/RIF Ultra | M. tuberculosis not detected (Sputum) | M. tuberculosis not detected (Gastric lavage) |

| Chest radiograph examination | Hilar lymphadenopathy | Hilar lymphadenopathy |

| Abdominal plain radiograph | Sentinel loop in the upper left quadrant | N/A |

| Abdominal ultrasound | Ascites | Ascites |

| Abdominal CT | N/A | Ascites in the abdominal and pelvic cavities, dilatation of the inferior vena cava (IVC) due to thrombus formation, a hypodense lesion with peripheral enhancement in the hepatic parenchyma, minimal nodular peritoneal thickening, and reactive lymph nodes in the inguinal regions |

| Ascitic MTB/RIF Ultra | M. tuberculosis not detected | M. tuberculosis not detected |

| Acid-fast bacilli | N/A | Negative |

| Ascitic fluid analysis | N/A |

Mono 94.3% Poly 5.7% Albumin ascitic 1.4 g/dL Albumin serum 2.9 g/dL Protein total 2.3 g/dL LDH 63 SAAG: 1.5 g/dL |

| ADA test | 58 U/L | 20 U/L |

| PCR TB ascites | N/A | Positive |

| Histopathology | Epithelioid histiocytes forming granulomatous structures and Langhans giant cells | N/A |

| Treatment |

2RHZE/4RH [FDC (75/50/150) 4 tablets + Ethambutol 20 mg/kg/day ~ 400 mg OD] |

2RHZE/4RH [FDC (75/50/150) 2 tablets + Ethambutol 20 mg/kg/day ~ 200 mg OD] |

Conclusion

Abdominal TB in children is complex and challenging to diagnose, requiring a high index of suspicion and a thorough, repeated diagnostic approach. Accurate diagnosis relies on a combination of history, physical examination, laboratory tests, imaging, molecular testing, and histopathology. While proper management can improve prognosis, the risk of long-term complications remains, highlighting the need for continuous monitoring to ensure full recovery and prevent recurrence.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the Department of Microbiology, Department of Anatomical Pathology, Department of Clinical Pathology, and Department of Radiology of Ngoerah Hospital, Bali, for their valuable support in sample processing and interpretation of diagnostic findings. Their technical expertise and collaboration were essential in completing this case report.

Ethical approval

This study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Udayana University (approval number 1755/UN14.2.2.VII.14/LT/2025). Written informed consent was obtained from the participants.

Source of funding

The authors declare the study received no funding.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global tuberculosis report 2023. Geneva: WHO; 2023.

- UNICEF. Desk review: pediatric tuberculosis with a focus on Indonesia. Indonesia: UNICEF; 2022.

- Sartoris G, Seddon JA, Rabie H, Nel ED, Schaaf HS. Abdominal tuberculosis in children: challenges, uncertainty, and confusion. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2020;9:218-27. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpids/piz093

- Chu P, Chang Y, Zhang X, et al. Epidemiology of extrapulmonary tuberculosis among pediatric inpatients in mainland China: a descriptive, multicenter study. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2022;11:1090-102. https://doi.org/10.1080/22221751.2022.2054367

- Lancella L, Abate L, Cursi L, et al. Abdominal tuberculosis in children: a case series of five p. Microorganisms. 2023;11:730. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms11030730

- Lukosiute-Urboniene A, Dekeryte I, Donielaite-Anise K, Kilda A, Barauskas V. Challenging diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis in children: case report. Int J Infect Dis. 2022;116:130-2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2021.12.342

- Cho JK, Choi YM, Lee SS, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of abdominal tuberculosis in southeastern Korea: 12-years of experience. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18:699. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-3635-2

- Laghari M, Sulaiman SAS, Khan AH, Talpur BA, Bhatti Z, Memon N. Contact screening and risk factors for TB among the household contact of children with active TB: a way to find source case and new TB cases. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:1274. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7597-0

- Dubois MM, Brooks MB, Malik AA, et al. Age-specific clinical presentation and risk factors for extrapulmonary tuberculosis disease in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2022;41:620-5. https://doi.org/10.1097/INF.0000000000003584

- Utami MDA, Purniti NPS, Subanada I, Mm AS. Faktor risiko infeksi tuberkulosis milier dan ekstraparu pada anak penderita tuberkulosis. Sari Pediatri. 2021;22:290-6. https://doi.org/10.14238/sp22.5.2021.290-6

- Çay Ü, Gündeşlioğlu ÖÖ, Alabaz D. Evaluation of cases with abdominal tuberculosis ın children: 10 years of experience from a single center in Turkey. South Clin Ist Euras. 2022;33:298-303. https://doi.org/10.14744/scie.2021.76093

- Rana S, Farooqui MR, Rana S, Anees A, Ahmad Z, Jairajpuri ZS. The role of laboratory investigations in evaluating abdominal tuberculosis. J Family Community Med. 2015;22:152-7. https://doi.org/10.4103/2230-8229.163029

- Kementerian Keshatan Republik Indonesia. Petunjuk Teknis Tata laksana Tuberkulosis Anak dan Remaja Indonesia 2023. Indonesia: Kementerian Kesehatan Republik; 2023.

- Concepcion NDP, Laya BF, Andronikou S, Abdul Manaf Z, Atienza MIM, Sodhi KS. Imaging recommendations and algorithms for pediatric tuberculosis: part 1-thoracic tuberculosis. Pediatr Radiol. 2023;53:1773-81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00247-023-05654-1

- Sinan T, Sheikh M, Ramadan S, Sahwney S, Behbehani A. CT features in abdominal tuberculosis: 20 years experience. BMC Med Imaging. 2002;2:3. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2342-2-3

- World Gastroenterology Organisation Global Guidelines. Digestive tract tuberculosis. World Gastroenterology Organisation; 2021.

- Seo YS. 2017 Korean Association for the Study of the Liver (KASL) clinical practice guidelines for ascites and related complications: what has been changed from the 2011 KASL clinical practice guidelines? Korean J Gastroenterol. 2018;72:179. https://doi.org/10.4166/kjg.2018.72.4.179

- Abid R, Oueslati I, Bousetta N, et al. Inferior vena cava thrombosis complicating tuberculosis. Ann Clin Case Rep. 2018;3:1534.

- Khaladkar DSM, Choure DAA, Jain DS. Abdominal ganglionic tuberculosis with inferior vena cava and common iliac vein thrombosis- A case report. Glob J Med Res.2019;29:11-6.

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO meeting report of a technical expert consultation: non-inferiority analysis of xpert MTB/RIF ultra compared to xpert MTB/RIF. Geneva: WHO; 2017.

- Slail MJ, Booq RY, Al-Ahmad IH, et al. Evaluation of Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra for the diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis: a retrospective analysis in Saudi Arabia. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2023;13:782-93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44197-023-00150-z

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO consolidated guidelines on tuberculosis: rapid diagnostics for tuberculosis detection; module 3: diagnosis. 3rd ed. Geneva: WHO; 2024.

- Dahale AS, Dalal A. Evidence-based commentary: Ascitic adenosine deaminase in the diagnosis of peritoneal tuberculosis. J Gastrointest Infect. 2022;12:57-60. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0042-1757402

- Mahajan M, Prasad ML, Kumar P, et al. An updated systematic review and meta-analysis for the diagnostic test accuracy of ascitic fluid adenosine deaminase in tuberculous peritonitis. Infect Chemother. 2023;55:264-77. https://doi.org/10.3947/ic.2023.0014

- Shen Y, Fang L, Ye B, Yu G. Meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy of nucleic acid amplification tests for abdominal tuberculosis. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0289336. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0289336

- Ahmad R, Changeez M, Khan JS, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of peritoneal fluid geneXpert in the diagnosis of intestinal tuberculosis, keeping histopathology as the gold standard. Cureus. 2018;10:e3451. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.3451

- Maulahela H, Simadibrata M, Nelwan EJ, et al. Recent advances in the diagnosis of intestinal tuberculosis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022;22:89. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-022-02171-7

Copyright and license

Copyright © 2025 The author(s). This is an open-access article published by Aydın Pediatric Society under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, provided the original work is properly cited.